I offer several examples of Collaboratic for purposes of illustration. The first example illustrates the simple problem model. The second example illustrates how Collaboratic is applied to a more complex problem. Other examples will be added.

A SIMPLE PROBLEM EXAMPLE:

My Broken Washing Machine

It might seem silly to use a broken washing machine as an introduction to a new way to approach public problems. But I want to illustrate Collaboratic with a very simple example. This example covers all of Collaboratic’s Problem-Solving Stages and ends with a clearly successful solved problem. I confess that I did not use Collaboratic to define this as a problem nor use it to guide my solution. Instead I simply dove in to fix the machine, figuring it out along the way. Only later did I apply the Collaboratic framework to see if this simple problem could be framed in terms of Collaboratic. It did, and it turned out to be an insightful illustration of the Collaboratic framework its and problem-solving process.

The Problem: I needed to clean work clothes so I had to wash them. I loaded the machine, like I always do, and pulled the knob: Nothing. My washing machine would not start. Being a homeowner I wanted to fix it myself. So I dove in to figure out what was wrong and I fixed it. In terms of Collaboratic. here is how the problem-solving process played out.

Stage 1: Formulation

Starting with the Stage 1 (Formulation) of the Problem-Solving Process, I lay out the Problem Foundations:

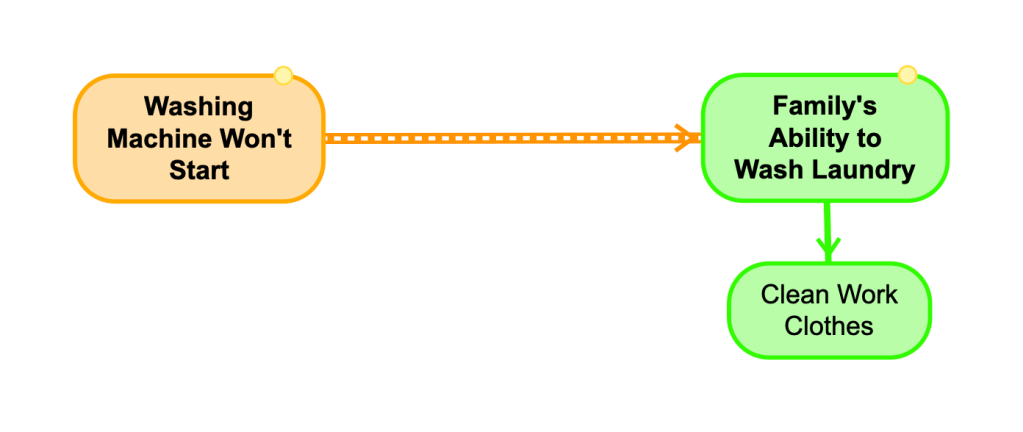

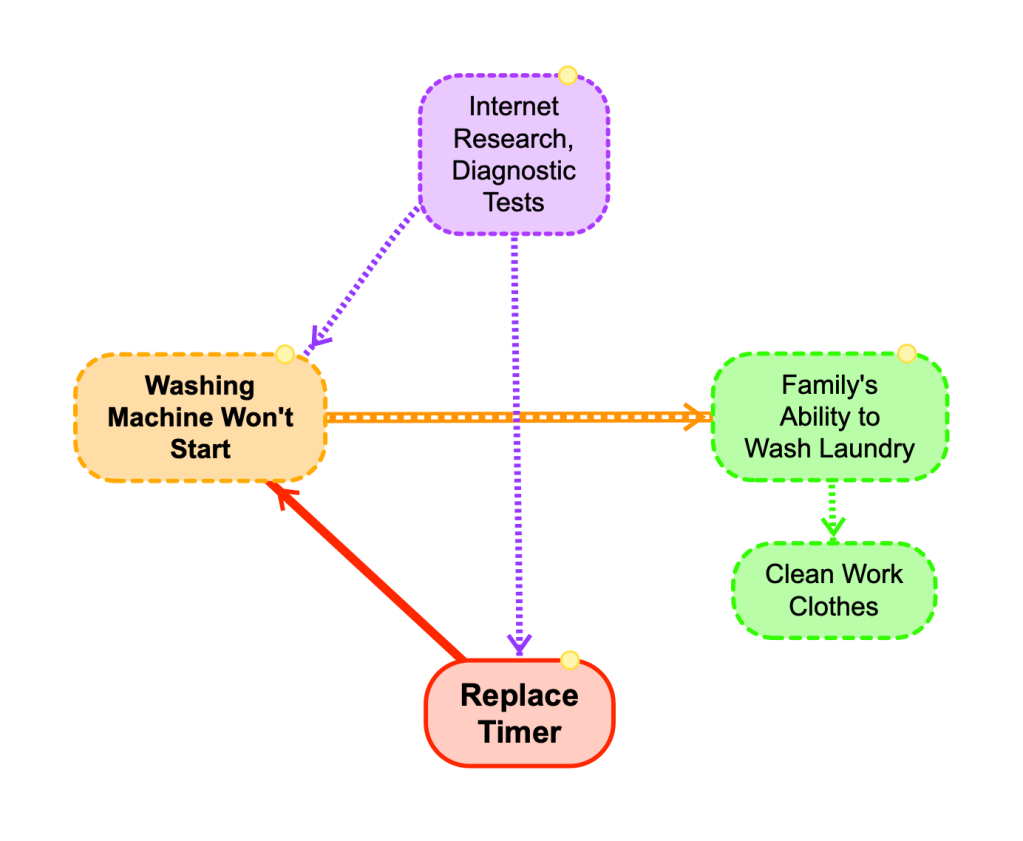

- The Imbalance is that the washing machine will not start. Not starting creates an impact, a harm, which is preventing my family’s ability to wash laundry, and me from washing that particular load of clothes. The harm is defined as not being able to wash the laundry. So the washing machine not starting creates the harm of not being able to wash laundry.

- My work clothes were my initial Object of Concern. But that quickly changed. Underlying this was something more important and less apparent: My family’s ability to wash laundry (and more specifically, as necessary and from the convenience of home). This became the primary Object of Concern. If that ability was intact, I could wash my work clothes. In this example, one Object of Concern (Ability to Wash Laundry) supports the other Concern (Work Clothes). Defining the Object(s) of Concern clarifies the problem and the nature of the solution.

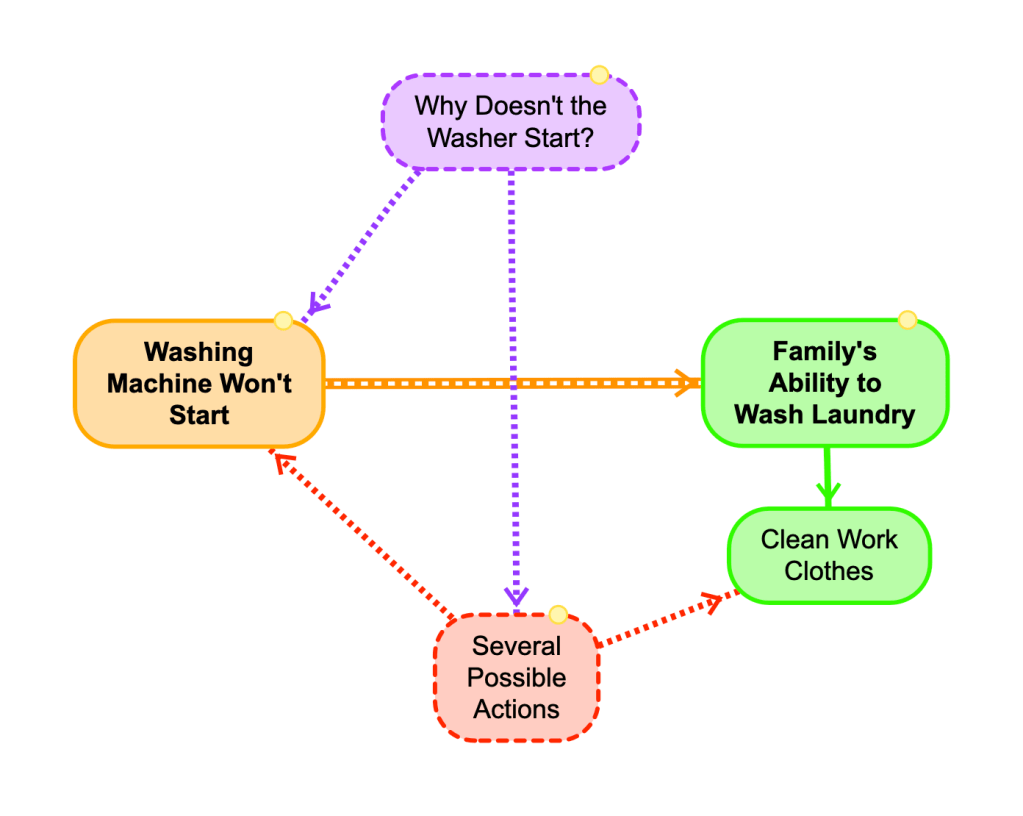

With the Imbalance, its Harm, and the Object of Concern defined, Formulation is almost complete: To complete the Formulation, I introduce the other two problem elements, Possibility of Action and Perplexity:

- The Possibility of Action and Perplexity: These go hand in hand. The Possibility of Action, at the outset, is a sense that something can be done to solve the problem, but exactly what to do remains a mystery. That mystery brings in Perplexity. Recognizing that there is a possibly of doing something indicates that I am confident enough to move forward and not simply give up. At the outset in this example, I know from experience that I have several choices of possible actions. I know that I could call a repairman (this remains an option should I fail), but I want to do it myself to save money. Outside of the repairman option, my range of options include fixing the machine or replacing it altogether. At this point, the exact action has yet to be determined because I do not know what is wrong and what to fix. And out of this unknown arises the Perplexity element and prepares the way for the next problem-solving stage.

Stage 2: Figure-Out

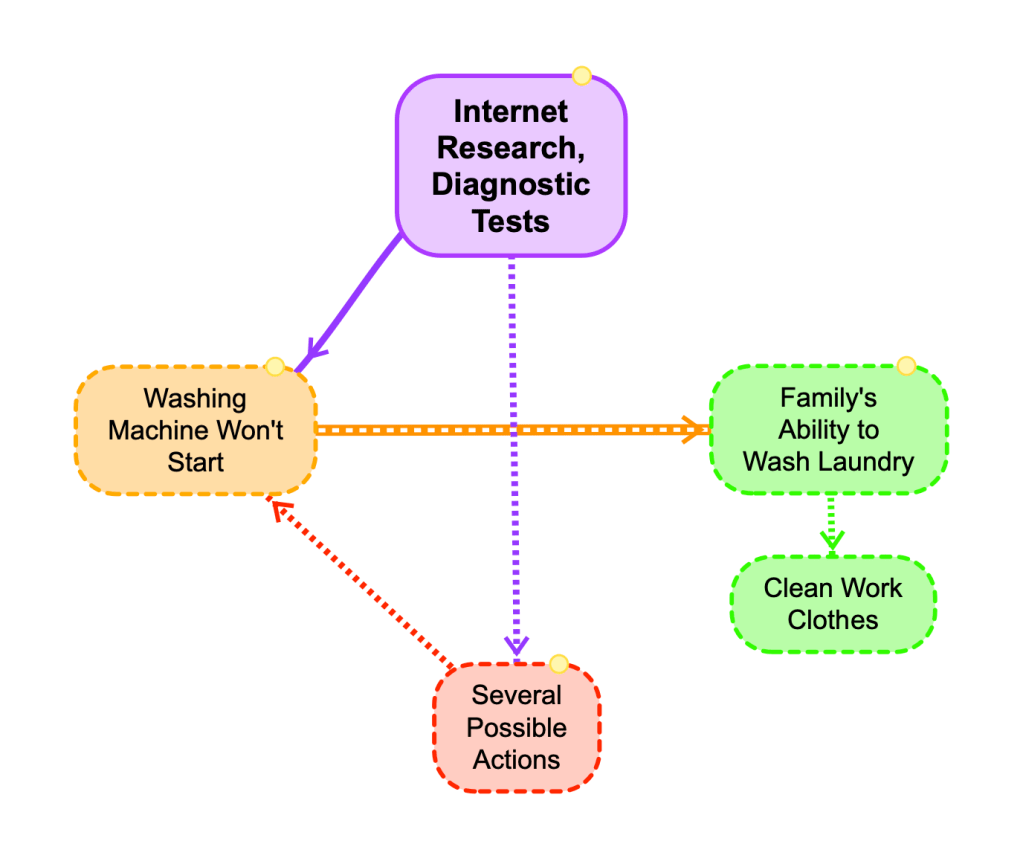

With my washing machine problem is now fully formulated, not knowing what do to is preventing my taking any remedial action except calling a repairman (and doing that is simply passing Perplexity on to the repairman as he would have to figure out what is wrong). In a sense, Perplexity is an obstacle that must be overcome. In this Stage, I put on my “thinking cap” and address the question of why the washer won’t start. Perplexity is directed at the broken machine, the Imbalance, in order to understand it better. Understanding the relevant system or systems and the cause of the imbalance is essential. I need to know how the washer works and what would produce this symptom. At this point in the Perplexity process, some background, context and history is helpful because it provides clues as to what went wrong: This is a 16 year old top-loading washer that had been operating normally before this malfunction. There were no warning signs or any unusual noises; it just would not start. A quick online search (my first Perplexity action) indicates that the fault is electrical in nature and identifies three common causes consistent with its sudden failure: no power to the machine, the timer is broken, or the lid switch is broken. All of these possible faults explain the sudden onset of this failure to start. Perplexity then leads to a series of diagnostic actions to determine the nature of the imbalance. These diagnostic actions are a form of inquiry whose purpose is to determine what exactly is broken and what steps must be taken to resolve the problem. In Collaboratic, the Perplexity element remains until the unknown is eliminated. Once I have diagnosed the fault and understand what to do, my Perplexity disappears and the Problem transforms into a Task (with an Action ready to implement). If a switch is broken, then it is a straightforward task to buy and install a new switch.

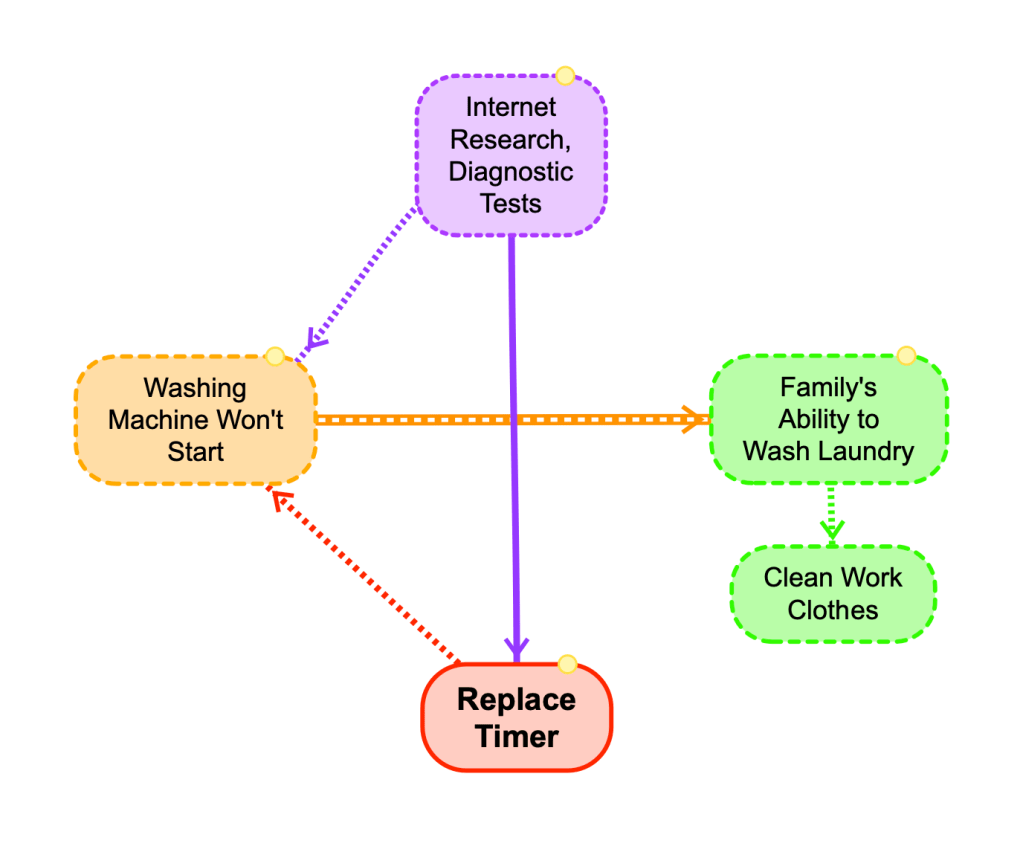

Figuring out what to do is a form of action in problem-solving and it necessarily precedes any fixing action. Therefore, my next step was to diagnose the Imbalance. I started with the easiest step which was to check the power, first with the circuit breaker (which was on), the outlet (which had power) and the then power cord (plugged in and firmly seated): The machine had power. This meant that the imbalance was internal to the machine’s electrical components (the lid switch or the timer). The next step was to check the lid switch which is wired in series with the timer. If that were broken it could be replaced, but it checked out fine. That left the only diagnostic option that the timer was broken. And the fix was straightforward: Purchase and install a new timer. With the fault identified, several things happen in quick succession: My Perplexity disappears (because I know what to do), the Possibility of Action is transformed into a specific Action (replace the broken timer), and the Problem transformed into a Task (buy a new timer and replace the broken timer).

Stage 3: Fix

Merely having a solution, while a relief, is insufficient. It has to be implemented. In this example, Stage 3 is straightforward. I purchased a new timer, installed it, plugged in the washer and the washer started up normally … Poof! Problem solved! In that instant, the Imbalance and its harm were eliminated, my Object of Concern was restored and I can now wash my work clothes (my initial Object of Concern). The problem then became a memory and part of my experience.

I want to highlight a few takeaways from this simple example that will carry forward to other examples:

- Objects of Concern add clarity to the problem and its resolution. They are the “why” of the problem and give purpose to the inquiry and remedial actions. Further, Concerns help determine the appropriate kind of action and the nature of the solution. In my simple example, fixing the washing machine will maintain my family’s ability to do laundry from home and my being able to wash my work clothes. If my primary concern were my work clothes, then the appropriate solution would be washing them at a laundromat and I could forget about fixing the machine. Finally, one further point is that Objects of Concern may be linked in a network of Concerns. Concerns can sometimes form networks of support as in this case, where “Ability to Wash Laundry” supports “Clean Work Clothes.”

- Systems produce imbalances. Imbalances do not occur out of nothing. Often, imbalances are the result of the malfunctioning underlying systems. An understanding of the underlying system(s), its components, and how they work is crucial to determining where to intervene in order to fix the failure. My washing machine is a rather simple system with electrical and mechanical components and it is hooked up to my house, itself a system, which provides electric power, hot and cold water, and a drain. Something among those components prevented my washing machine from starting. Understanding these systems and pinpointing the fault is necessary to solve the problem.

- History often provides clues as to what went wrong and how things came to be the way they are. My washer did not make odd noises or display any indication of something gradually wearing or failing. Instead, my washer ran normally until it didn’t, and that suggested an electrical failure rather than a mechanical failure. That was the place to start the diagnosis. Sometimes undoing an event in the past will fix an imbalance in the present (e.g., plugging it back in, if the plug were loose). The broader implication of history is that maybe what happened in the past can inform remedial action.

- In Collaboratic, Perplexity is a type of action. The diagnostic steps that I took were actions that I did to understand the Imbalance. Those diagnostics steps were integral to solving my problem, and it necessarily preceded the action I took to replace the timer. So the take-away here is that there are two kinds of action in problem-solving: A figuring-out kind of action and a fixing kind of action. The figuring-out kind of action is represented in Stage 2 of the Problem-Solving process, named, oddly enough, Figure-Out. Stage 3 of the Problem-solving process is represents the fixing kind of action.

Hopefully this simple example clarifies Collaboratic. In cases of simple problems an individual can quickly and easily navigate all the elements intuitively making Collaboratic unnecessary, as I did with my broken washing machine. However, when a problem is more complex, and with many people and points of view involved, Collaboratic may serve as a useful guide to help people arrive at a common understanding and perhaps an effective collaborative solution.

COMPLEX PROBLEM EXAMPLE:

California’s Ongoing Water Problem

This example shows how Collaboratic’s framework and methodology might be applied to a complex problem. California’s water problem has many Imbalances, many Objects of Concern, a mix of Possible Actions and specific Actions already underway, and many Perplexity elements that still need figuring out.

Still working on it.